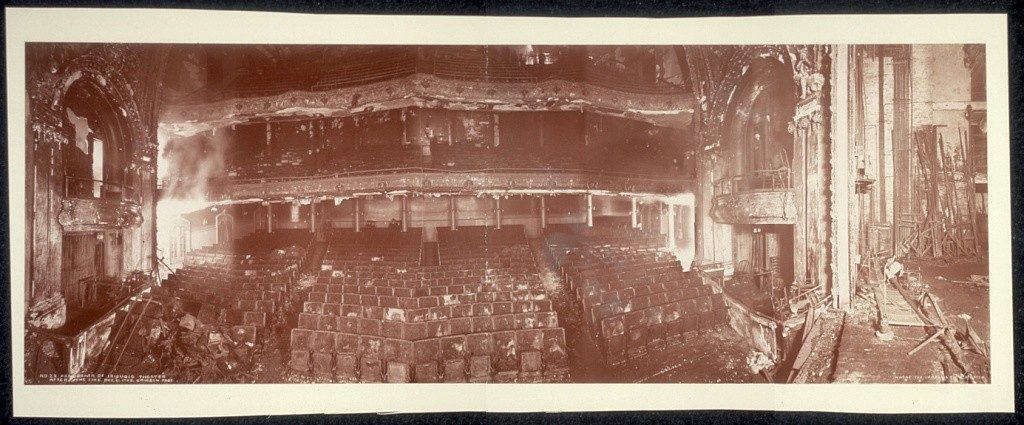

On December 30, 1903 a children’s matinee of Mr. Bluebeard, starring Chicago native Eddie Foy, was featured in the newly built Iroquois Theatre. Being the week between Christmas and New Year’s, attendance was high, especially women and children out for an afternoon diversion.

The brand new theatre was advertised as being absolutely fireproof. The advertisements did not mention that the venue was not finished.

- Fire escapes had no exterior ladders to get to the ground.

- The flues at the top of the stage house were boarded shut, unable to serve their purpose of venting flame and smoke.

- The lack of an adequate fire alarm, automatic sprinklers, marked exits, or suitable fire extinguishing devices contributed to the disaster.

The show was over-attended. All of the 1,700 seats were sold, and with extra “standing room only” tickets and house passes, some estimates place total audience at around 2,100. People were sitting in the aisles and blocking the exits.

At the beginning of the second act, one of the calcium lights ignited a drapery. Attempts to put out the fire with a primitive flame retardant were useless. The fire quickly spread to the fly gallery high above the stage, moving from backdrop to backdrop, igniting everything in its path. Meanwhile, the show went on as Foy attempted to calm the audience ordering the orchestra to keep playing.

When it became apparent that the fire could not be controlled, stagehands lowered the asbestos fire curtain—but it snagged on a light reflector that extended outside of the proscenium. (It was later discovered that the fire curtain was mostly made of paper and would have been useless against the fire.)

The result was panic. Audience members stampeded for exits hidden behind draperies with hard-to-open doors. Accordion metal gates had been installed near the exits to the lower level. Those who fled from the balconies encountered the accordion gates, locked to keep them from sneaking down to better seats. When a cast member opened a backstage door, the result was a fireball fed by the inrush of air. The lights went out in the theatre as it burned. The bodies piled up as desperate patrons attempted to flee the few choked exits.

While the Iroquois served to make for better laws and practices, and even inspired the invention of the crash bar that we see on modern doors today, a hundred years later a new tragedy would again illustrate how bad things can get in a very short time.

The Station nightclub was located in West Warwick, Rhode Island. The popular venue was licensed for 404 occupants. On February 20, 2003, there were 462 people in the audience to see the band Great White—like the Iroquois, the show was over-attended.

Unlike the Iroquois, this fire was the result of an intentional pyrotechnic effect using a device known as a gerb. These devices (sometimes referred to as “fountains”) typically emit a shower of sparks for a specific duration and distance. In this instance they were for 15 seconds at 15 feet.

The sparks ignited the acoustic polyethylene/polyurethane foam insulation around the stage area and within one minute the blaze reached a flashover point. The result was a fireball emitting highly toxic levels of hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide gases in which 2 to 3 breaths could prove fatal.

Ironically, in the audience that night was TV cameraman Brian Butler (WPRI), working with a reporter on a news piece about nightclub safety. His video captures the start of the fire and the escape of the patrons. It shows, in real time, just how fast and dangerous fire in a gathering place can be. It is a grisly teachable moment. The video is on YouTube. Be warned: It might be disturbing for some viewers.

This fire resulted in 230 people injured and 100 fatalities.

In the criminal investigation that followed, it was found that the band Great White used pyrotechnics without permission in at least four states. The band said it had permission from the club but that claim was denied by the club owners. In the end, no permit for pyrotechnics was ever issued. And almost all of the rules in the NFPA 1126 standard outlining indoor pyrotechnics use were ignored.

Both of these fires illustrate how quickly things go bad. As theatre professionals we are obligated to ensure our colleagues have a safe working place, and our patrons can safely enjoy the show.

- Are any of the elements that caused these fires being duplicated in your performance space?

- What standards do you have in place to guard against fire?

- What more can you do as a venue owner, producer, or technician?

Coming up next, easy and economical ways to make your theatre or place of gathering safer.